The Holy Trinity

A sermon preached by the Rev. Nils Chittenden

Sunday, May 22, 2016

Today is Trinity Sunday. The complicated theology is coming thick and fast at this time of year. Three Sundays in a row. The Ascension, Pentecost and now the Trinity. The Ascension and Pentecost – two theological events that we find it very hard to comprehend, and the Trinity – a theological concept that we find it very hard to comprehend.

The Trinity presents us with one of the most mind-bending concepts in Christian theology, but there are some pretty extraordinary concepts that we follow as Christians. We go through them each week when we say the Nicene Creed.

In fact, we say the Nicene Creed so often that we go onto auto-pilot and the concepts in it fail to have very much impact on us.

But for a moment, just consider that we believe – and publicly declare – that we believe that an omniscient being outside of the boundaries of the space time continuum undertakes the in vitro fertilization of a young peasant woman from a small and relatively insignificant place within, biologically-speaking, our own epoch; and the resulting child, for the first and only time in the history of the known universe, having died, comes back to life and is then subsumed into a cloud of mist never to be seen again in bodily form, but present for eternity thereafter in an equally real but non-tactile form in order to inspire and inform our thoughts and actions.

When put like that, it does perhaps indicate why sharing our faith is so often not very easy for us. It is difficult to understand, difficult to explain and – for those hearing it with no prior knowledge – difficult to accept.

For a short moment, I’d like you consider how you would respond to someone new to the concepts of Christianity asking you to explain to them the Holy Trinity. In fact, people may have asked you that very question. How on earth do we begin to explain a concept that has challenged even the very finest theological minds over the centuries?

The Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev

I’ve certainly been asked over the years if Christians believe in three Gods. It’s a logical enough question. After all, we do say that we believe in God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Spirit. And when we see the Holy Trinity in our minds’ eye, we do tend to see three figures, don’t we. Certainly, the representations of the Holy Trinity in art often have three figures. Pictures, for example, like the famous 15th century icon of the Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev (above) that has three beautiful angelic-like figures seated around a small meal table.

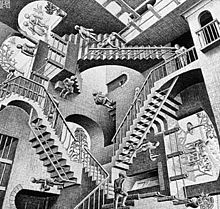

Relativity by MC Escher

Yet, there are also depictions of the Trinity in art that don’t follow that route, but try to depict three simultaneously as one. If you are familiar with the paintings of MC Escher (right), you’ll know the kind of thing I am talking about. Like those pictures, the Trinity seems to defy rational explanation. Indeed, it does defy rational explanation, because our capacity to reason, impressive as it is, is too small and limited to take in the fullness of God. And that is just one of those things that we have to learn to live with.

Yet, mind-bending as it is, I am not saying that we shouldn’t therefore try to grapple with the concept. It is important for us to try and understand it more, because it will help unlock other mysteries of the Christian faith – and tell us more about the nature of God.

But where does the concept come from in the first place?

The word Trinity does not appear in the Bible, but we do know that Jesus told people he was the Son of God, and when Jesus prayed to God, he called him ‘Father’, and Jesus also told us that when ascended to the Father, he would gift us with the Holy Spirit that emanates from the Father, so it was inferred that God was three ‘persons’ – the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

On the face of it, this does seem to suggest three separate beings. But at the beginning of St John’s Gospel, we are told that Jesus is the word of God that existed before the world came into being, and that the word was with God, and that the word was God. And later in St John’s Gospel, Jesus tells his disciples that when he leaves the earth and returns to his father in heaven, he will send what he calls, ‘another comforter’. In so doing, Jesus describes himself as a comforter sent by God, and that when he disappears from the earth, God will send another comforter. Since Jesus, is sent from God, and actually is God, so, too, by implication is this other comforter, the Holy Spirit. Therefore, the theorizing goes, the Holy Spirit also is actually God.

Since the Bible also tells us that there is only one God, and since we learn through Jesus and the Gospels that God is, variously, a Father, a Son and a Spirit, this is how we arrive at God being one entity with three personas. Or, to use the language of classical theology, one being in three persons.

Now, theologians have chosen their words very, very carefully indeed. Choose one slightly different word, and the ramifications are huge.

All of this does sound like people arguing over something really, really esoteric. It certainly sounds that way, but let me tell you by way of some church history, about how one tiny word can have immense consequences.

That tiny little word is this: ‘filioque’. It’s a Latin word. It means, ‘and the Son’.

A 16th c. fresco of the Council of Nicaea

In the first half of the first century AD, as Christian theology developed, and people tried to make sense of what had been said and taught by Jesus, and written down by others, the young Church tried to get its theology more organized and systematized. In 325 AD, as you will know from reading your bulletin each week, representatives of various churches from around the Mediterranean got together at Nicaea in what is now northern Turkey to try and resolve bunch of questions and get some standardization. Some ideas got ruled in, and some got ruled out and, eventually, the main communiqué that they produced and released was a statement of belief which, in fact, became so widely accepted that we will be saying it in a few minutes’ time. When we say the Nicene Creed – i.e. the creed put together by the Council of Nicaea, we will say it as it was written in 325, but with one tiny little extra word. And that word is ‘filioque’, which crept in over the second half of the first century and which, by the year 1054 had caused so many huge arguments between different parts of the church that in the end the Eastern branch of the church, based in Constantinople, gave the Western branch of the church, based in Rome, what amounted to an ultimatum. Stop using the little extra word, or we’ll split off from you and do our own thing. Guess what happened? And that split still exists, and the Eastern branch of the church still doesn’t use that one tiny little word. And the West does. And it has now, after a thousand years, become one of those seemingly irreconcilable differences that keeps the Roman and Protestant churches separate from the Eastern Orthodox churches.

Let me ask you to look at the text of the Nicene Creed in your service booklet. Then look down towards the end and you will see the phrase, ‘I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son.’

If I were to take you down the road to the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Stamford now, and ask you to take a look at the Nicene Creed in their service booklet, you would find that it said simply, ‘who proceeds from the Father’. In other words, that the Holy Spirit comes from the Father, but not from the Son.

Why on earth is this so important? Some people would say that it’s important because if the Holy Spirit only comes from the Father, and not from the Son, then it diminishes the Son, and makes it seem that he is less equal than the Father. Others say that if the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, then it is subservient to the Son.

In a world full of pain and of people simply looking for God, why on earth does this kind of thing matter so much?

As with so many things, it’s not so much the detail of the argument that is the main thing, but what it represents. I don’t think that God minds very much whether or not we include, ‘and the Son’, or not when we say the Nicene Creed, and it is a tragedy of monumental proportions that the churches of the world even fell out over this, let alone stopped talking to each other.

But it’s what’s behind it all that really matters, which is this: that we all long to know who God is, and we yearn to know more about him. You can tell the really important things in life, because they are the things that people get most tied up in knots about. People argue about the Holy Trinity so much because what is a stake is how we describe God. And how we describe God affects how we comprehend God in our hearts, and how we comprehend God in our hearts is the most important question we’ll address in our lives.

Ultimately, then, this is all of huge consequence.

Because if Jesus isn’t actually God, but just a nice guy who went around doing good, then we might as well all go home right now.

But if it is that God himself in the person of Jesus died on the cross for us, and conquered hell, and neutralized for ever all of the devil’s power over us, then there’s hope for all us, and hope for everything, and everyone in this world.