Thinking outside the box

A Sermon preached by the Rev. Nils Chittenden

Sunday, FEBRUARY 4th, 2018

There are three types of people in this world. Those who are good at math, and those who aren’t.

Often we get labeled at an early age, and then increasingly funneled through the structures that consolidate those characteristics. Sometimes, these early labels become self-fulfilling prophecies and come to define who we become. As you know, I’m a musician, and have led choirs, and I have had countless conversations with people who’ve always wanted to sing – and had nice voices – but who were told at any early age that they didn’t have any musical abilities and a nasty voice. They’ve gone through life with this appalling misdiagnosis.

Now, sometimes, it isn’t a misdiagnosis – don’t get me wrong. There were five math classes in my school, the top one for people who really knew what they were doing and the bottom one for those for whom math was just one great big perplexing mystery. Let’s just say that I was in the class that matched my ability.

But the point is that we seem as a society to have an innate desire to classify people into neat boxes, boxes which often stay with us for life. Sometimes these boxes aren’t a bad thing – they can help to focus us into building us up in those things we excel at. But sometimes these boxes constrain us – constrain our ambitions, or keep yearnings buried deep within us. This is why thinking ‘outside the box’ is such a good thing. Although it has been appropriated as a business cliché, it is essentially a virtue that we are called to as Christians – that is to say that we are called to see people and situations as much broader and infinitely more complex than the convenient labels that society gives them.

Anyway, you may be wondering what this has to do with anything. I’ll come on to that momentarily. First, a little bit of context, etcetera, on the gospel reading.

The reading that we have just heard from St Mark’s Gospel actually follows directly on from last week’s reading. Jesus was in the synagogue in Capernaum, by the shores of the Sea of Galilee, where he engages in some teaching, and an exorcism is thrown in for good measure.

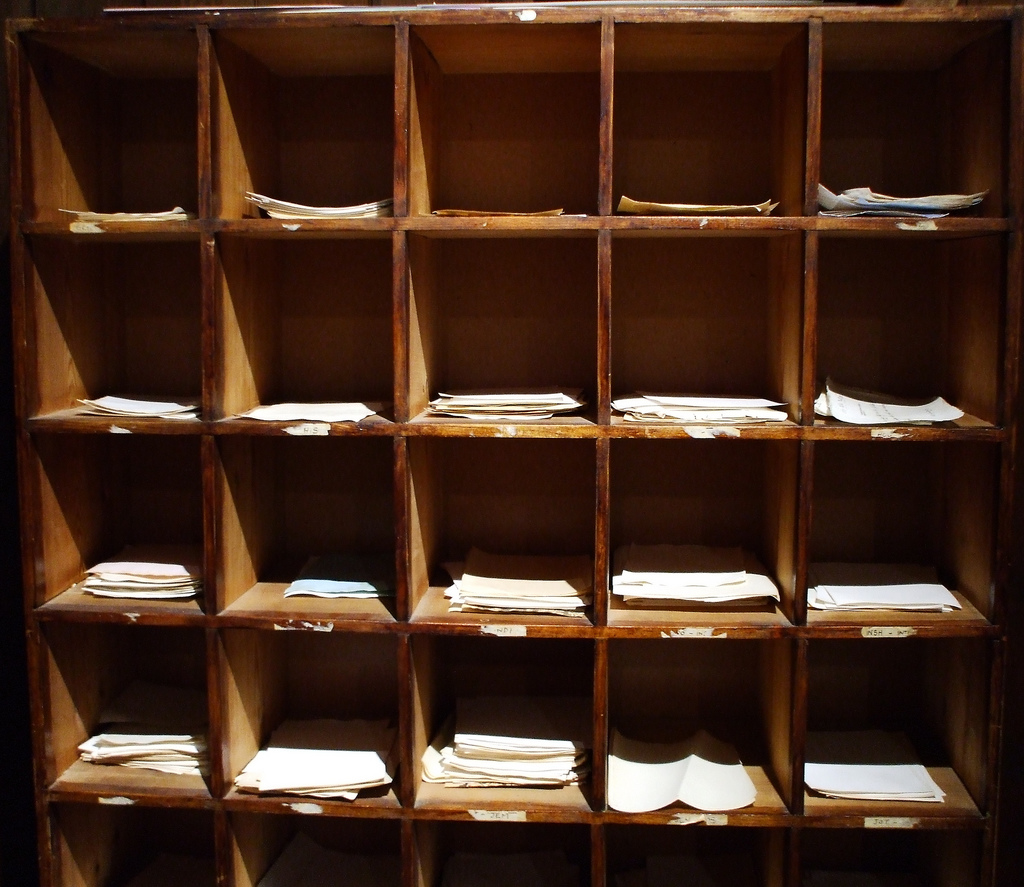

The excavated site in Capernaum believed to be the house of Simon and Andrew.

Then he leaves the synagogue, and visits the house belonging to the mother of the disciple Peter’s wife. As I seem to mention at any opportunity, Kelly and I had the pleasure of visiting the Holy Land back in 2012, so this scenario from the gospel reading is all very much in my mind’s eye. Capernaum is a very small place, as it was in Jesus’ day, and the synagogue is literally round the corner from where it is traditionally held that the house of Simon and Andrew was. Archaeologists have done a lot of excavation, and you can see the walls and the rooms of that house (pictured, above), and easily transport yourself back two thousand years and imagine Jesus taking the one minute walk between the synagogue and the house, stooping in through its low, narrow doorway into its darkened, domestic interior, where the woman in question is in bed with a fever.

Already, there are some interesting questions being raised for us. We never think of Simon (i.e. Peter) – or the other disciples, come to that – being married; but evidently at least Peter was, in order to have a mother-in-law. No mention has been made prior to this point, of Peter’s wife. We think of Jesus and his disciples being this bunch of guys on a bit of a road trip around the place. But the likelihood is that there were married disciples and that spouses were also on these journeys. In fact, in his first letter to the Corinthians, the apostle Paul tells us that Simon Peter’s wife did in fact accompany him on some of his missionary journeys, including to Rome. Peter was by no means the only, and probably not the last, Pope to have had a wife.

Anyway, back to the story. Simon Peter tells Jesus that his mother-in-law is sick. She is in bed with a fever. Jesus immediately goes to her bedside, and without any drama, fuss or grandiose procedures, he simply takes her by the hand, helps her to her feet, and she is restored to health. And, the next thing she does is to serve them dinner.

Now, it would be easy at this point for me to launch into some clever comments about how the minute the woman was healed she had to wait hand and foot on the guests. Typical, one might say. Can’t the poor woman get five minutes of R & R? But no, she has to fix dinner. And, of course, the men don’t do anything. She’s the woman, so of course she has to serve them.

And, yes, that’s fair comment, isn’t it? Like I was saying at the outset, people do get placed into the roles that society expects of them – and first century Palestine was a rather patriarchal society, and there were very distinct gender roles, which actually intensified over the following centuries, which is doubtless why although Jesus clearly had plenty of female disciples, it’s only the men that really get the air-time and why we don’t hear anything more about Simon Peter’s wife (or even realize that he had a wife) and why we don’t know her mother’s name. Thus it is that the Bible has been used for centuries to legitimize the forcing of women into the background, and into purely servile roles and, at worst, into simply be regarded as the property of men, to do with as their husbands please.

'The Healing of Simon Peter's Mother-In-Law' by Rembrandt van Rijn.

So, it would be easy for me to critique this passage as portraying Simon’s mother-in-law as being forced into a her servile gender-based role.

But here’s the thing. Perhaps serving people dinner was what really enlivened Simon’s mother-in-law. Maybe that’s what really made her heart sing, made her flourish, fulfilled her. Who’s to know? But I have a feeling that that could well be the case. Because what Jesus was most concerned with was bringing people life in all its fullness. That’s what he says in John’s Gospel: ‘I have come that people may have life, and have it in all its fullness.’

What I believe Jesus does in every single encounter where he transforms a life, is to bring that person life in all its fullness. Physical health is one thing, and her sickness was certainly holding her back from life in all its fullness, but let’s consider that Jesus also brought back to her the ability to live life in all its fullness by doing that which allowed her to flourish – which was serving the guests in her home, making them feel comfortable and rested.

Of course, Simon Peter’s mother-in-law remains defined by history as a dinner-server who had a fever, just as Einstein is defined in our minds as a guy with crazy hair who worked on complex algebra, and just as Ghengis Khan is defined as a tactically astute psychopath who was good with horses. And so we reduce these people to one-dimensionality. And we do it, do we not, so often. It doesn’t matter who it is… erm, let’s see… I don’t know… Walt Disney, Saddam Hussein, Kim Kardashian, Mother Theresa – we don’t always allow for people to be fully-rounded human beings, complex, multi-faceted and - yes – cherished by God as made in his own image.

As you will have noticed, I often start our Sunday Eucharist by asking you to reflect on what it is that has brought you here today, and that you can bring to this holy place everything that’s on your hearts and minds right now which may be hope, or fear, or joy, or sadness but which, really, is a mixed and complicated soup of all of those things.

In our second reading today, St Paul talks – albeit in a rather convoluted way – about how he tries to put himself in the shoes of those that he is sharing the gospel with, whether that is as a slave, or a Jew, or someone in poverty – to quote the examples he gives. In short, Paul says, he is ‘all things to all people’.

By trying to understand what makes someone tick, Paul is able more effectively to minister to them, and I think that it is good advice.

Unless we take the time to try and understand what it is that makes people tick – makes them do what they do – good and bad – they will remain one-dimensional, and defined by us in narrow terms that do not allow for the fact that everyone is entitled, as a Child of God, to live life in all its fullness.